All Sermons

- Details

-

Series: Scottish Reformation Rally 1960

-

Duration: 14:17

-

Additional file: 125a.txt

Preliminary Address 1 Scottish Reformation Rally

in commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the Reformation in Scotland

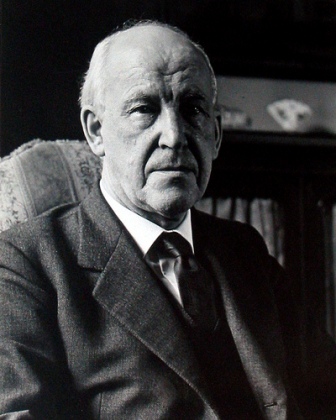

and contains the introductory remarks by the chairman, the Reverend Professor A.M. Renwick, D.D.

of the Free Church College in Edinburgh and the main address by Dr. D. Martin Lloyd-Jones, MRCP

of Westminster Chapel in London.

Ladies and gentlemen, it is indeed a very great privilege indeed to preside over this large gathering here this evening.

As you know, we are here in order to commemorate in this meeting the 400th anniversary of the Scottish Reformation.

This is one of the first of these meetings to be held in Scotland.

But from now onwards, many such meetings will be held in all parts of the country right into the winter months, we hope.

It is a good thing to commemorate the Reformation.

Perhaps we don't all realize the greatness of that happening which we call by that name.

I'm afraid there are some today who think it was even necessary.

In order to prove to people that the Reformation was necessary, all we have to do is to go to old Roman Catholic documents.

We cannot do better than go to the minuets of the various councils, the provincial councils of the Roman Church here in Scotland before the Reformation.

And we'll find described there a condition of things which reveals to us in an almost incredible fashion the deplorable condition of our country

and the deplorable condition of the Church in those ancient days before the Reformation took place.

There is a line of argument to take to go to those documents written by the Roman Catholics themselves and enshrined in the records of that Church.

And there we'll find ample evidence to show what sort of a land our land was before this great event took place.

You will find, for example, in the records of the provincial council of the Roman Church held here in Edinburgh, in the year 1549, a reference to the condition of the clergy at that time.

It's a very general reference, referring to almost all ranks of the clergy.

These are the very words of that ancient document.

And we are told in that document of the corruption of morals and profane lewdness of life which existed among almost all ranks of churchmen.

Now that's a rather remarkable statement, coming as it does from the Roman Catholic, describing the condition of things which existed then.

Thomas McCree, in his sketches of Scottish church history, a most readable book, and also Fitz Scotty, a much older church historian,

tell us of what happened to the vicar of Dollar, a cultured and godly priest of the Roman Church.

The vicar of Dollar, Thomas Porritt, usually known as Dean Thomas, was an outstanding man in the church at that time.

He was canon of Inchcombe and occupied a very honorable position in the church.

But he did what was very unusual in those days. He began to preach every large day.

You may not be aware that for nearly a thousand year old rites and ceremonies, but there was no preaching.

Gavin Dunbar attempted to preach in the open air in the town of Eyre, because they found that the Protestant preachers were producing a great impression by preaching.

The Bishop of Glasgow, Gavin Dunbar, went down to Eyre to preach there in the open air in the square.

And he could only utter one or two sentences, and then had to apologize because he couldn't go any farther.

He promised to do better next time, and implored the people to continue having him as their bishop.

While the vicar of Dollar was a very different type of man, he began to preach every large day.

And for doing so, he was hauled up before his bishop, the Bishop of Dunkell, Bishop Crichton.

The bishop seemed to have been a rather kindly old man, and he addressed Dean Thomas, saying in my joy,

I love you, and because I love you, I want to tell you the way in which you should act and behave.

They tell me, he said, that you're accustomed to preach from the epistle, or from the gospel, which is read in church for the day.

And he went on to tell Dean Thomas that he thought he was making a very big mistake in preaching.

He said, if you go on preaching, then they'll expect us to preach.

And he also complained that the Dean didn't take the cowl, or the uppermost garment on the bed,

when any of his parishioners died, he wouldn't do that, but that was usually done by the priests of those days.

And the bishop complained of that proceeding. And he said to Dean Thomas, I'll tell you what you can do.

If ever you find a good epistle, or a good gospel, then you can preach from that, now and again.

Dean Thomas replied, I have read all the gospels and all the epistles very carefully,

and as far as I am concerned, I cannot find any among them that is good.

As far as I know, all the gospels are good, and all the epistles are good.

And the reply of the bishop is very illuminating as to the condition of the church at that time.

He replied, I thank God that I know nothing of either the Old Testament or the New Testament.

And so I adhere simply to my partuis, and my pontifical. The partuis was his breviary.

That's all he wanted. He didn't want to have anything to do with the Old Testament or the New.

Now you'll find in many of those ancient Roman Catholic documents complaints about,

complaints about the ignorance of the clergy.

That ignorance was so grave that when Bishop Hamilton, in the year 1552,

published a catechism with the approval of all the bishops in Scotland,

the preface to that catechism laid it down that all the vicars and curates and others

who were going to read that catechism to the people for their better edification

must be very careful to practice it, and to practice it carefully, to rehearse it constantly,

lest in the midst of their reading they should stumble and make fools of themselves

because they weren't able to read the catechism.

That reveals to you the condition of education

among a large number of the clergy at that time in the days preceding the Reformation.

Now that was a great thing that the Reformation did for Scotland.

The greatest thing of all was that it simply called back the people from the mass,

from all the rites and ceremonies of the Roman church which had obscured the scriptures,

called back men from thrusting in a human priest,

called them back to read for themselves the word of God which was then put into their hands

and which had been prohibited to them before then in their own language.

The Reformation was a going back to the word of God.

In other words, it was a going back to the position of the church as that existed

in the days of the apostles, a return to the doctrines and the position of the early church,

both in doctrine and in worship.

Let us never forget that that's what the Reformation did for men,

and that in itself was something very great indeed.

And another great thing that the Reformation did was to emphasize,

as it had not been emphasized in apostolic times,

to emphasize the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers.

Before then, the people were at the mercy of the priests.

The Roman church had increased the number of sacraments from two,

which is the New Testament number, to seven.

And only the priest was fit to administer these sacraments.

And they believed that the grace of God could only come through the sacraments.

The grace of God came to you at baptism, you were regenerated at baptism,

when the priest sprinkled a few drops of water on your face.

Every one of the seven sacraments brought the grace of God in some way or another to the people,

until finally, at death, extreme unction was administered,

which was the last of those sacraments.

The grace of God came, and their conception of that grace was something, more or less,

automatic, something mechanical that came simply because the priest administered those rites.

But that will reveal to you how the people were at the mercy of the priests.

If a man believed that his soul would be lost,

unless he received those sacraments at the hands of the priest,

and particularly if he did not attend mass,

you can readily realize how that man would feel that everything depended on the priest,

that he must constantly look to the priest.

The Reformation swept all that away,

and taught men the tremendous doctrine of the priesthood of all believers,

that the Lord Jesus Christ, through his death on Calvary,

opened the way into the holiest of all.

And that through his death, men are invited to come boldly to the throne of God,

through Jesus Christ our Savior.

You can hardly imagine what a difference those teachings made in Scotland.

It was a rebirth of the Scottish people.

It's not too much to say that the Scotland that we know owes almost everything to the Reformation.

Our people were strengthened in character.

They were given courage.

They were given a new insight into the purposes of life.

They were given a new independence.

They were even given new political conceptions.

And that was precisely one of the great things that the Reformation did for Scotland,

that it it arose in the Scottish people a feeling of democracy,

a feeling of the equality of men before God.

And I'm proud to think that John Knox was a man who was a Democrat to the fingertip.

And we shall never understand John Knox if we don't remember that.

Remember that Queen Mary represented absolutism.

She also represented the spirit of the Roman Church.

John Knox represented the spirit of the New Testament.

He represented that the democratic spirit that is taught in the New Testament.

The Queen stood for one ideal, John Knox stood for another ideal.

John Knox felt that he was sent there by God to do a great work and he did it.

And I cannot imagine any man who has ever served God more sincerely than John Knox.

And it's recognized in all hands I think by fair-minded people

that there were two men in the great Reformation struggle of Scotland

who were men who had no axe to grind, men who sought no glory for themselves,

men who took the stand they did because they believed it was right to do so,

and because they believed that God called them to do so.

These two men were John Knox and Sir William Chercory of Grange.

For many years they stood side by side in the great struggle.

But in the end Sir William Chercory of Grange fell under other influences for a time.

But just before he died he recognized that John Knox was right,

that John Knox was indeed a man of God and that John Knox had spoken the truth to him.

Now it's not for me to take up time because tonight we have the great privilege

of having with us Dr. Martin Lloyd-Jones of Westminster Chapel, London.

He's the minister of a great and renowned congregation.

He's a man greatly owned by God in our generation,

a man who not only ministers to a large congregation but whose voice is heard in every part of Britain,

a man whose influence increases as the years go by.

And we are thankful to God that this evening once more

we have the very great privilege of having Dr. Martin Lloyd-Jones here with us.

And in your name I thank him for his presence and we pray that God may be with him

as he delivers to us his message this evening.

Now with regard to giving thanks to people I should like to say this,

that a very considerable number of people have helped us very much indeed in making

preparations for for this meeting. You'd probably be surprised if you

knew how many things have to be done in order to organize a meeting of this kind.

And some of our friends have gone out of their way to to be helpful.

And to them tonight without mentioning names I express our wholehearted gratitude.

Now we are now to wait upon you for your offering but in order to save time I'm going to ask

Mr. J.L Sutherland to make a few intimations at the same time

that the offering is being taken up. Mr. Sutherland.